We quickly get used to the sound of alarm bells.

My smart watch keeps vibrating, every single hour, reminding me to stand up. I turned on the feature because I know sitting for too long is unhealthy.

And when I say I know, I KNOW.

I know it in my head. I’ve read the studies. I feel it in my bones. I get all of the stiffness, soreness and general discomfort.

They say sitting is the new smoking.

But when the alarm goes off, as it does every hour, my bum stays firmly planted in my chair. I barely even blink. I don’t even recognise the words on the screen. It has the same effect as a fly buzzing near my ear momentarily before floating into the distance.

We act as though our comfort is too sacred to sacrifice, even though surely something in the back of your head knows that the comfort you refuse to sacrifice today will become the discomfort you’re forced to live with tomorrow, once the warnings fade away and you’re stuck with the inevitable consequences.

How quickly do alarm bells fade into background ambiance? Ask your morning alarm. Or the notifications from your habit app.

At scale, ask our planet.

We hear the planet is dying and nod our heads. Oh no, we once gasped. What a terrible plight. Now, telling you about climate change is like telling you it’s Tuesday. I sure hope somebody does something about that! But our bums stay firmly planted in our chairs.

I’m not asking you to pull on your supersuit. I’m just commenting on how frequently notification systems aimed at shocking us into action quickly become mundane.

Like the figurative frog in the frying pan (real frogs don’t do this), you sit still as the heat is cranked up slowly because the pain isn’t immediately noticeable, and by the time it is, you’re stuck in the mollifying hammock of convenience. What might have once shocked you, becomes almost invisible.

Think of how quickly we become desensitized to violence, war and economic crisis.

The habituation effect

After repeated exposure to a stimuli, a person's response to it begins to diminish. This is a process known in behavioural psychology as habituation. The more you see something, the more forgettable it becomes.

Noise from an outdated air conditioning machine might irritate you when you first enter a room, but 20 minutes later you may hardly notice. It goes back to something I’ve discussed previously - the brain is an expensive machine constantly making predictions of the world around us. Something new and unexpected is immediately jarring. But if it’s constant, you won’t spend any additional time processing it.

Despite our incredible intellect, we spend the majority of our days on autopilot.

How frequently do you check your phone? I want you to guess, and then quickly check - on an iphone you'll see it under screen time.

Here’s mine - I’d been up for 3 hours and thought I’d ‘barely touched’ my phone since waking up. Yikes!

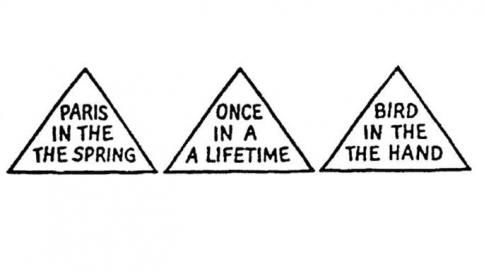

Here’s another quick demonstration. Read the sentences below out loud:

Notice anything odd? Even a tiny bit weird? They all have repeated words! You may have felt a slight discomfort you couldn’t place, but often you don’t notice these words because it makes more sense to read “Paris in the Spring” than “Paris in the THE THE Spring”. Your brain didn’t bother waking you up to that fact. It just processed whatever was easiest. Your eyes glazed right over them and hardly noticed a thing.

On a more mundane level, we see logos every day, but most people can’t recall the details of the relatively basic Apple logo.

Let’s try one more brain spinner. Think about your office at work. Imagine your chair, your desk, wherever you like to sit. Now - where’s the nearest fire extinguisher? Or a fire exit? There’s a good chance you’ve passed it a few hundred times. I’m not making this example up - there was a study asking participants the same questions and they didn’t have a clue. And then the researchers asked them to go and find them, and people still failed.

If I showed you five rooms and one had a snake in it, you’re probably going to remember the snake. And you’ll remember any rooms that obstacles you could use to keep it at bay. Yet while we know that a fire extinguisher may save our lives, because we don't use them very often we become numb to their warnings.

Think about how you listened to the air safety instructions the first time you were on a plane. I've taken a few hundred flights at this point, visiting over 40 countries, and I don't even take my headphones off to hear what they're saying now. You already know what they're going to say, right? "Something something the air mask falls, put on your own before helping others, something something exits" and then you go down the big yellow slide. It's background noise - and that becomes dangerous.

The consequences of habituation can be severe, and in certain cases, this might mean the difference between life and death. There's a dreadful and heartbreaking phenomenon that happens frequently enough to have its own name: "Forgotten Baby Syndrome," in which a sleeping newborn is left behind in a car. People get so accustomed to a routine that they completely forget the addition of a baby.

The things you choose to ignore

Occasionally though, our amnesia is selective. We habituate intentionally because there are things we don’t want to notice. When we set an alarm for ourselves, we’re not just setting a prompt or notification. Frequently we’re attempting to install a time machine, hoping that when the bell rings, a more productive version of ourselves will emerge. The one who actually wants to wake up, be productive and be on the hook for getting things done.

Sometimes we grow accustomed to our personal failures. When you fail so often you accept it as a natural consequence. We make small adaptations to our identities. You may accept that you’re “a little lazy”, “not great with people” or “have anger issues”.

More frequently though, we reject and ignore our failures, sweeping them under the carpet. The alarm becomes invisible because it is painful to realise and acknowledge we are acting in a way that is inconsistent with our personal narrative.

You ignore the fact that your first alarm failed to provoke action. You can try again next time. This way, you can protect your ego and self-image. Just move on, you tell yourself. So you don’t dwell on it - you spend little time thinking about what caused the behaviour and how to avoid falling into the trap going forwards.

You pile some leaves over the hole you fell into and march forwards, thinking you can simply avoid it in future.

Eventually, however, we must realise that by covering up our failures, not only are they shrouded from others, but we become blind to them ourselves. The more you ignore it, the bigger the hole gets.

You will keep falling into the widening pit until you decide to take responsibility for it. It’s not enough to put loud and vibrant signs up, warning of the danger. You must cordon off the area, to avoid stumbling into it while drunk, angry, confused, or otherwise preoccupied.

Then, and only then, can you commit to doing the real work.

Fixing the hole

You must fill the hole. Plug the gap. Fix the deficiency. You can’t ignore it, hoping that it fades into the background. Otherwise, the hole becomes too large to climb out of, and the deficiency becomes your identity.

So you must spend real and intimate time with the hole.

It was once something random and unexpected. Yet each time you fell into the hole it grew wider. It became more you-sized. Now it’s your hole. You’re on the hook.

Whether your failure is procrastination, anger, greed or fear, the holes we fall into all operate the same. Whatever problem it is that you eventually become accustomed to sliding into effortlessly. That thing that makes you simultaneously both comfortable and disgusted.

You need to know your hole in order to fill it. Any gap you miss just leaves room for duplicating the error.

Filling a hole also takes good materials. It may take discipline, confidence, persistence or punctuality. It may even be a combination of all those things. But if you can find it in the wild - if you can see examples of them in action, you can replicate them. You can find the person on the other side of your alarm's 'time machine'.

So grab a shovel. Pull on your boots. Find some friends who can help. Figure out where the good soil is and how to get some. And slowly fill that hole.

Further Reading