I've recently had the pleasure of immersing myself in great short stories from Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol.

Prior to this past month, I'll admit I hadn't explored much Russian literature beyond Checkov in the last decade or so, and even my limited reading was prompted by an English class reading list.

Alyosha the Pot was one such story by literary giant Leo Tolstoy. In an analysis by George Saunders on Tolstoy's craft, something stuck out to me.

The tale follows a simple boy—Alyosha—perhaps the most hard-working, earnest and unquestioningly faithful young boy in all literature.

He toils away from a young age, smiling in the face of insult and scarcity. He never talked back or wavered in his diligence and contentment with the cards life gave him. In some ways, the consummate stoic.

After being denied the potential happiness of young love, he responded with a smile and returned to his work as though nothing had ever happened. Not long later, he slipped on some ice and fell, injuring himself and dying shortly after.

Saunders imputed that in his reading of the main character's demise, the cause of death could be more than mere accident.

It was as though Alyosha had subconsciously surrendered, resulting in the kind of uncharacteristic laxity that would result in him taking leave of the world.

Although I'm extrapolating far further than Mr Saunders may have ventured, it was a reminder that self-limiting beliefs can have both a psychological and physical effect on us.

Sometimes what we believe to be inevitable comes to pass simply because that is all we have prepared for.

Brain in a box

In Issue 29 I shared some insights from Lisa Feldman Barrett—one of the world's most highly cited scientists in the fields of neuroscience and psychology. One of the biggest revelations I've gleaned from her work is that our brains are essentially locked in a dark box, receiving streams of data about outcomes in the world (sensory data) with no way to determine the causes.

We assume that we act in response to things around us. We think we sense first and move second but neurologically that isn’t true - our brain is constantly trying to predict what actions to take next based on past experience and then using sensory data to confirm or amend that prediction.

Your brain prepares the firing of neurons > to prepare a set of internal changes in your body > which will support a set of physical movements > and as a consequence, it changes a set of neurons responsible for tasting, smelling etc. > to prepare an experience before the sensory data arrives. When the sensory data arrives it is merely confirming the prediction or changing it.

Everything you have ever experienced is your brain predicting and learning from statistical irregularities.

An example I love sharing at cocktail parties (I'm lots of fun), is that our skin has no wetness receptors. When we feel sweat or drops of rain on our skin, our brain is simply making predictions based on temperature and touch, for which we do have receptors, and weaving them together into the experience of wetness. When you feel something wet, it's just a hallucination cooked up by your brain connecting narrative to the sensory data.

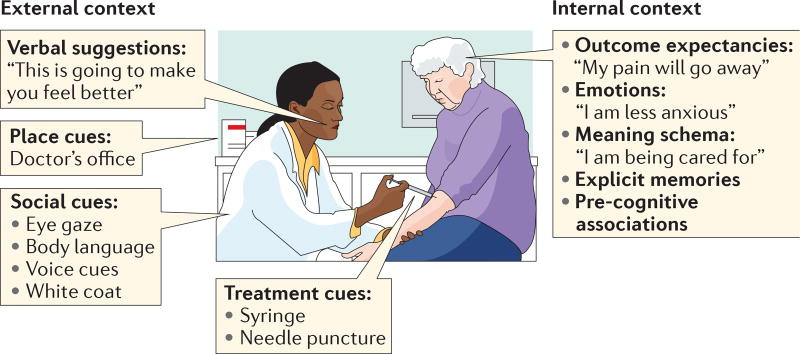

The placebo effect

In scientific circles and common parlance, we commonly refer to the placebo effect as a sign of failure.

A placebo is used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of treatments and is most often used in drug studies. For instance, people in one group get the tested drug, while the others receive a fake drug, or placebo, that they think is the real thing. This way, the researchers can measure if the drug works by comparing how both groups react. If they both have the same reaction — improvement or not — the drug is deemed not to work — Harvard Health

The element of this we often underestimate is the acknowledgement that your brain, with no additional resources, can often replicate the effects of billion-dollar pharmaceutical marvels.

A 2014 study published in Science Translational Medicine explored this by testing how people reacted to migraine pain medication. One group took a migraine drug labeled with the drug's name, another took a placebo labeled "placebo," and a third group took nothing. The researchers discovered that the placebo was 50% as effective as the real drug to reduce pain after a migraine attack.

Despite references to the placebo effect being relatively commonplace, I don't think we pause enough to fully appreciate that simply by believing something will make us better, our brain can reconfigure the associated sense of pain and neurological discomfort. Beyond that, even when we know we are taking a placebo, the mere act of putting a pill in our mouths (i.e. behaviors we associate with healing) can be half as effective as actually taking medicine.

Double-edged sword

These effects go both ways. Some studies have shown that when you're expecting to experience negative side effects, your body can start to exhibit them. In a study of arthroscopic knee surgery in Texas, patients with sore knees were assigned to one of three operations—scraping out the knee joint, washing out the joint, and doing nothing. In the 'nothing' operation, doctors gave patients anesthesia as though the surgery was about to take place, and made three little cuts in the knee, giving the illusion of instrument insertion. In some variations, the patients were cut and then stitched back up. Two years post-surgery, the patients who had the fake operations reported the same level of pain relief as patients that underwent real surgery.

This also happens on a dietary level - one study showed that people who drank a milkshake thinking it was healthy exhibited caloric impact as though it was healthier, while people who were told the same milkshake was unhealthy exhibited greater caloric impact. Suddenly ‘you are what you eat’ becomes ‘you are what you think you eat’.

In Japan, another study was carried out on participants who were allergic to poison ivy. They were rubbed on one arm with a harmless leaf but were told it was poison ivy and touched on the other arm with poison ivy and told it was harmless. All of them produced allergic reactions to the harmless leaf and only two reacted to the poison ivy they were told was harmless.

The power of crowds

Many of you may have heard comparisons of the coronavirus pandemic to the Black Plague or the Spanish Flu. A pandemic you may be less familiar with is the phenomenon that struck mainland Europe in the 14th and 17th centuries: choreomania—the dancing plague. Hundreds of years apart, droves of people suddenly found themselves stricken with uncontrollable jerking of limbs. Once taken over by the dancing bug, sometimes thousands at a time, they danced until they became exhausted and collapsed. Occasionally the dancing was accompanied by stripping, howling, or even laughing and crying to the point of death. This was speculated to be one of many mass psychogenic illnesses, i.e. where physical symptoms with no known physical cause are observed to affect a group of people.

In what became known as the "June Bug" outbreak in June 1962, over 60 workers at a dressmaking factory in the US experienced symptoms including severe nausea and breaking out on the skin. Entomologists and others were called in to discover the pathogen, but none was found.

Researchers later also linked the rapid rate of contagion with the apparent reasonableness of the bug infestation theory and the credence given to it in accompanying news stories. That is to say, the more it was reported on and believed, the faster it spread.

A similar outbreak occurred in the data center of a university town in 1974. Ten of 39 workers smelling an unconfirmed "mystery gas" were rushed to a hospital with symptoms of dizziness, fainting, nausea and vomiting. No gas was detected in subsequent tests of the data center.

It makes me wonder, at a time when mental disorders are often worn as badges on social media and university campuses, how much of our suffering might be a result of socialization and zeitgeist. This is in no way demeaning the reality of those experiences, but only a consideration of the extent to which psychology and disorder can be socially influenced.

More strength than we know

When we feel sick we’re only feeling our body’s attempt to fight an intruder or pathogen - even when the intruder doesn't exist. The psychological discomfort of a situation we're in, or an odd smell, or a slight disconcertion, can suddenly lead to a headache or other physiological ailments. We anticipate, and so we feel.

Sometimes the effect of what we don't have time to process is just as miraculous. You may have heard news stories and anecdotes of parents lifting cars and boulders to save relatives in life or death situations. I even once read of a woman going toe to toe with a polar bear to save her son and his friends. Hysterical strength is a legitimate phenomenon, and the secret is relatively simple.

We've survived as a species by processing fast and reacting early. Our brain simulates hunger and thirst being quenched long before the nourishment is processed by our bodies. We can feel pain at the sight of blood. Fatigue, fear and pain are all tools in the brain's toolkit for self-preservation.

That's how marathon runners get a second wind, how boxers bounce back in the final round, and how sprinters find an extra burst of speed in the final moments of a race. If fatigue was purely physical this would be impossible. The truth is that we spend almost zero time operating at maximum capacity in any area. Our brain safeguards against it in order to protect us.

I've written before about allostasis and how the brain prepares for the metabolic outlay. I've talked less about how the brain sheds abilities as we grow.

Babies are born with the capacity to speak every language on the planet, but selectively lose some ability as they focus on the linguistic traits they are exposed to and taught to practice. Years later, as an adult, you may find some difficulty learning Spanish, Japanese, or Xhosa because you can't quite move your tongue the way you need to. In the same way, you may develop back pains because you can't squat the way you did as a child. Our brains are expensive machines - we are born with a large pot of capability but the brain will pare back what isn’t used in the same way adults lose childlike mobility through inactivity. We limit going broad so that we can go deep. Extra capacity is for emergencies.

Telling better stories

Words can affect us more than we realize. As children, we use words to signpost ideas and systems as we make sense of the world. The part of the brain that processes language is actually the same place we make predictions and do our body budgeting. Because of allostasis and the way the brain allocates resources in advance, words can have a big impact on our body budgeting, breathing, immune systems and more. That's why hearing a familiar name can trigger a physiological response. It could be butterflies in your stomach, or fear and panic.

This applies not just to external chatter, but to the internal narrative. The stories we tell ourselves, often narratives enforced by repetition, can result in physiological changes in our body and a profound impact on real-world outcomes. Hearing a test will be hard can make you more worried about it, more anxious when studying, and more distracted in the exam. Hearing your new boss is a tough cookie can make you more nervous and more prone to make simple mistakes.

Stress is just your brain predicting a big metabolic outlay. Often we can generate feelings of anxiety and distress which throw off our performance before we've even had a chance to act. The more we anticipate and mentally prepare for negative outcomes, the more likely we are to bring them about through action or inaction.

Many of these reactions we learn from experience, but others from socialization. The media we consume creates data for us to make inferences from. We’re told what to predict and how to react. Curating your consumption and looking for the resulting patterns you're adapting is crucial.

Control what you consume. Tell yourself better stories. Push through the fear and pre-emptive fatigue. Remember that it's all in your head!

React to this issue by clicking an emoji: 😍 | 🤯 | 👍 | 😴 | 👎 | 😡

If you have any nuggets to share about the brain and self-imposed limitation, I’d love to hear from you! Reply via email, leave a comment or send me a tweet!

Read on for this week’s recommendations >>

Reading list

Books I’ve read/seen/will impulsively buy and add to my “to read” shelf on Goodreads. Recommendations from newsletter readers are always welcome:

- Skin in the Game by Nassim Taleb - read. A highly opinionated read, but a great reminder of how perspectives and outcomes shift when you have skin in the game, vs merely predicting and opining.

- Show Your Work by Austin Kleon - impulsively bought. Probably the only book I’ve bought in paperback at least three times - for myself and for friends.

- The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Galloway - wishlisted. Someone just made a very compelling case for reading this. On one level a tennis bible, and on another, a guide for clear thinking, concentration and competing at the highest level.

Things I’m loving

Films and shows:

- Invincible - Without saying too much, I’m pretty sure I watched the last 20 minutes of the first or second episode with my mouth open. The original comics largely parodied traditional superheroes, but there are a lot of dark twists and grim realities at play.

- I May Destroy You - A gripping drama I took way too long to get around to. Michaela Coel at her best, both acting and directing.

Resources:

- Audible - I’ve just hit 33 books this year, almost halfway towards my yearly goal. It’s an irreplaceable tool I’ll consistently recommend. Plus, when you sign up for a trial you’ll get a free book of your choice that you can keep forever even if you cancel.

- NordVPN - if you value your security online, or just hate ads, cookies and online content blockers (Location-specific content on Netflix, Hulu, etc.) set your devices free with NordVPN. They’re about to end their sale so it’s your final chance to grab 70% off before prices increase!