In the Capitalist plutocracies that dominate the West, time is largely conceptualised by virtue of value extraction.

Time feels short and fleeting. I am as equally ensnared as anyone. I listen to podcasts and audiobooks at 3-3.5x speeds. I’m constantly looking for ways to minimise, optimise and hedge against time haemorrhage. Everything needs to be instant, fast and automatic.

A worldview built around rapid transactions and a highly competitive market for both employment and trade force us to continually upskill and seek additional labour, thinking about what we must learn or build to avoid being left behind.

The final nail in the coffin is the fact I currently pay $30 for Superhuman, an email service with carefully manufactured exclusivity and a waitlist of 275,000 people promising the fastest email experience ever made.

In my efforts to disentangle myself from the manufactured speed of the digital age, I’ve been giving more thought to what we can learn from African concepts of time.

Things Fall Apart

'Black/African timing' is a widely acknowledged joke in the Black community, referring to a stereotypically lackadaisical approach to punctuality from Black people across the global diaspora. I can't tell you exactly where that comes from, but it makes an interesting parallel against historical time constructs across Africa.

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart gives us a good insight into how time was conceptualised in pre-colonial West Africa - specifically, Igboland in Nigeria.

The book narrates that during planting season, Okonkwo worked daily on his farm from Cockcrow until the chicken went to roost. On page 19, Achebe writes that “the drought continues for eight market weeks…” On page 22, Ikemefuna was ill for three market weeks. Then on page 23, we see that Ikemafuna came to Umofia at the end of the carefree season, between harvest and planting. On page 27 we learn that “yam, the kind of crops, was a very exacting king. For three or four moons, it demanded hard work and constant attention from cockcrow till the chicken went back to roost”.

We can see that time here is constructed solely in relation to the actions it necessitates.

In East Africa, per John Mbiti, a Professor of African Philosophy, the Ankore people of Uganda had similar constructs of defining time based on related events.

To the Ankore, cattle was the ultimate measure of wealth, and as a consequence, each day was constrained by those needs:

6 am is Milking time. 12 pm, the time for cattle and people to rest. 2 pm, the time for cattle to drink water. 5 pm, the time when cattle return home.

Similarly, the Latakia tribe of Sudan named months by temporal characteristics. October is called the sun because it is very hot. December is called give your uncle water because water is scarce. February is called let them dig because that’s when fields are prepared for planting. June is called Dirty Mouth because children can now begin to eat the new grain and in doing so get their mouths dirty.

Hakuna Matata

According to Mbiti, in many tribes across Africa time was a two-dimensional phenomenon, running contrary to the linear time of the West where both past and future were infinite. To Africans, “time is simply a composition of events which have occurred, those which are taking place now and those which are immediately to occur”.

It brings to mind the phrase Hakuna Matata popularised by Disney’s The Lion King. In one memorable scene, Rafiki, the wise baboon, whacks Simba on the head with a stick and then tells him not to worry about it because “it’s in the past”. Hakuna Matata means no worries. It is the mental act of remaining in the present.

In our modern world, many of us have the benefit of not needing to be constrained by cattle or seasonality, yet we still don’t define our time by the things that are important to us.

For most of us, time is dictated top-down by society. The bulk of your day is mandated by work, and the remainder is spent recuperating in order to return the next day. We’re taught that the only way to free yourself from this in the long term, is to sacrifice anything else you value such as family, friends and socialisation in the short term.

How would our relationship with time change if we constrained it based on our values?

Seasons for everything

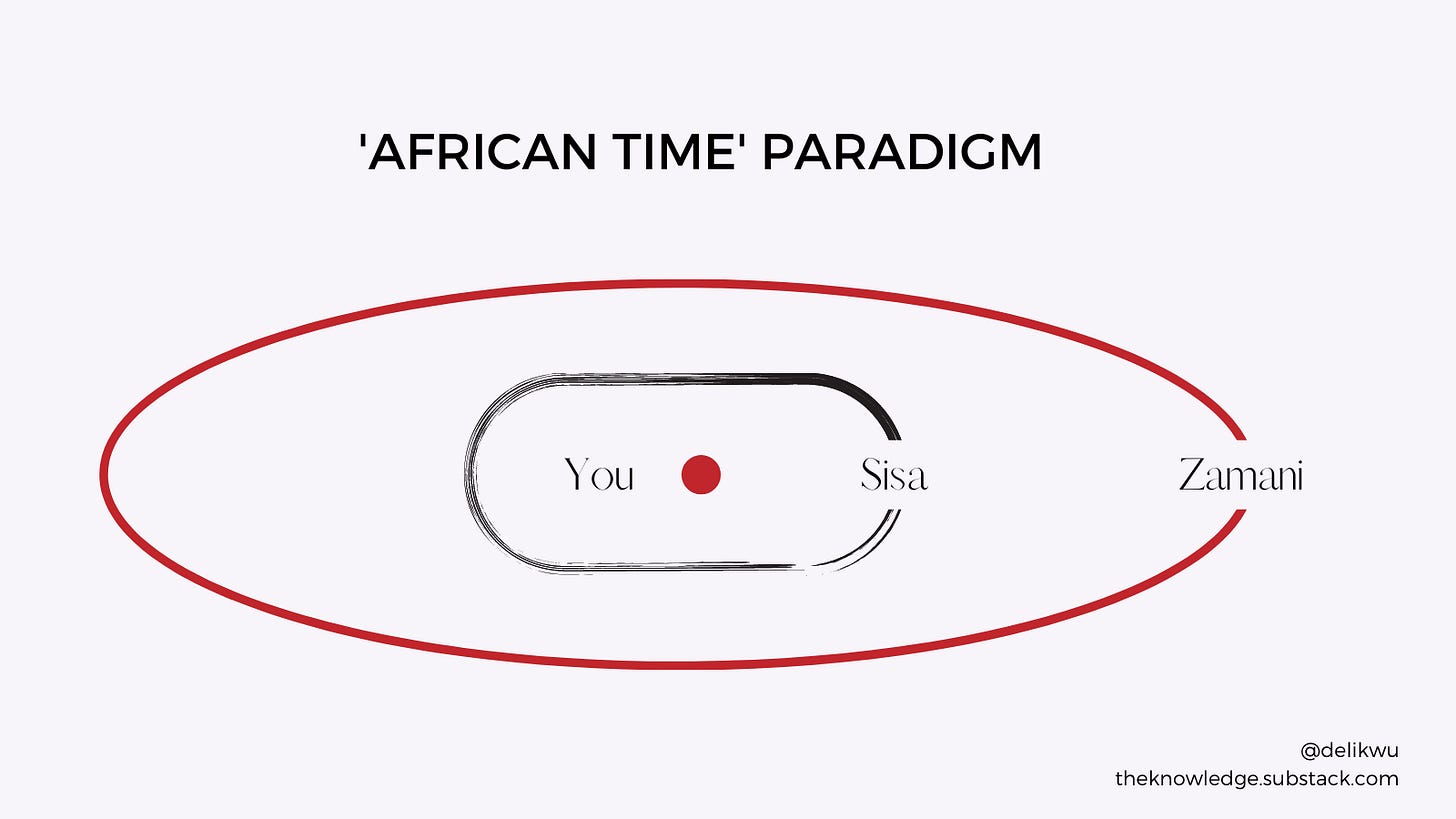

Two Swahili words present a paradigm of the flow of time and our relationship with it.

In common verb tenses, 'Sisa' (also known as Sasha or Sasa) is a word covering the immediate. It carries a sense of the present and things near it, including the immediate past and immediate future. It is the time within touching distance-time that can be experienced. Micro time. 'Zamani' by contrast carries a grander scale of past present and future. This is Macro time.

Sisa disappears into Zamani, but before events become incorporated into the Zamani, they must become realised or actualised within the Sisa dimension. Once the events have taken place and their immediate aftermath has been experienced, they move backwards from Sisa into Zamani. The boundless nature of Zamani makes it both a future of endless possibility and the graveyard of time. "Zamani is the final storehouse for all phenomena and events, the ocean of time in which everything becomes absorbed into reality".

Interestingly Eckhart Tolle presents a similar yet opposite construct when considering the modern (Western) concept of time.

To most people the present moment almost doesn't exist, because what they are really interested in is the next moment, or the one after that. So they live always towards the future. They live, towards the next moment. And unconsciously, they regard the next moment, the next moment in time they need to get to, as more important than this moment - not realising that the future moment they are so desperate to get to will soon become the present. We fail to recognise that the future has no form of existence other than as a thought form. Something outside the present moment.

In the African time construct you are centred in the immediate. Time lives within touching distance. The far future comes when it may, and the far past is easily forgotten. In the Western time construct, we are pre-occupied with the future, and the immediate only exist to be sacrificed for tomorrow.

When we are only looking to what lies ahead, we can fail to maximise our experience of the present moment. We miss out on the joy of being present. I made reference to Mo Gowdat's happiness equation in Issue 17 - Managing your cognitive bandwidth. In his book, Mo represents happiness as 'your perception of events in your life minus your expectations of how life should behave'.

Applying that construct here, I think that by always trying to live in the next moment, our perceptions, experiences and expectations will be flawed. As much as we might dream of it, happiness doesn't exist in the conceptual future - happiness only exists in moments of lived experience.

Make time for joy

Michelle Obama shared an enlightening thought I loved about planning for joy, even in your darkest moments.

“We are taught to plan work, but we also need to plan joy. You might think you should not feel joy when other people are suffering, but you need to find joy or else risk burning out...think about what you are going to do this week that is going to make you selfishly smile."

Time is constantly moving and can't be paused. The future quickly becomes the past if we don't plan intentionally to live in the present.

Protect and preserve time for what you value

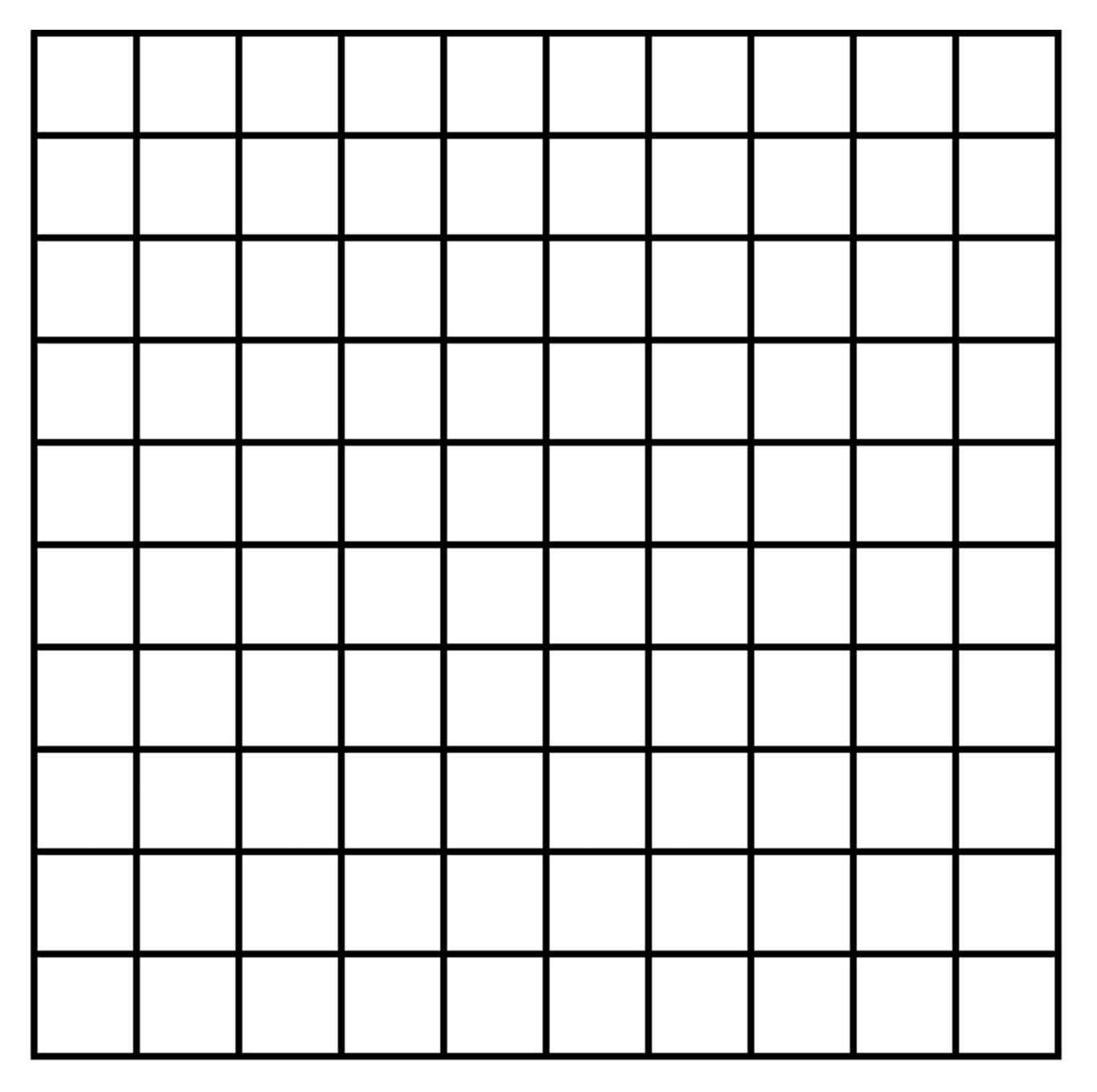

If time isn’t protected, the need for labour will encroach rapidly. In a 2016 blog post, Tim Urban visualised time as a day with 100 10-minute blocks (once you subtract 7/8 hours sleep). When you layout every 10-minute block you have in a day, you realise just how scarce time is, and how important it is to both prioritise and enjoy how you spend time:

In a similar diagram from another post, Tim broke down how this scarcity can also apply to relationships. During your first 18 years of life, you're likely to spend 90% of your days interacting with your parents. After going to university and moving to another city, you might only see them five times a year each, and two days each time on average. If you lay out those person-days on a grid, you realise how little time you really have left to spend time with those you love. By the time we leave high school, many of us have already used up +90% of all the time we will ever spend with our parents.

Generate serendipity

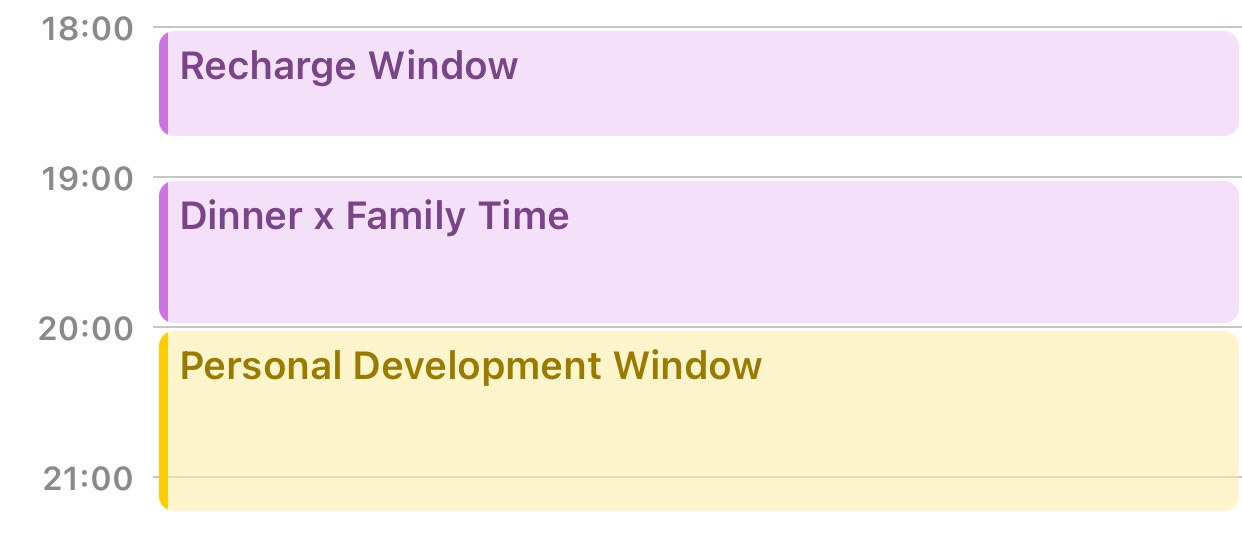

A friend of mine recently shared how she was making time for joy through calendar blocking, something I touched on in 'Issue 6 - Learning to live on 24 hours a day'.

When we are being rushed by ruthless scheduling, we have little time for the moments of serendipity that make life awesome. Instead of seeing what time is leftover once others have had their pick of our prime moments, we should actively set apart time for thinking, spending time with loved ones, taking walks and being at rest. Engage in unrushed, atelic activities. Try meditating or mindfulness. These reflective moments are important not only for wellness, but because it's also when our subconscious is most effective. By taking intentional time to ruminate we are investing in our future productivity, memory-building and idea-generation.

Use your blocks of time wisely. Define moments based on the events and values you plan to experience. Be present in each moment. Live on African time.

Sidebar: scroll to the bottom for a chance to win some delicious African coffee this week :)

If you have any thoughts on time management, mindfulness or serendipity, I’d love to hear from you! Reply via email, leave a comment or send me a tweet!

Reading list

Books I’ve read/seen/will impulsively buy and add to my “to read” shelf on Goodreads. Recommendations from newsletter readers are always welcome:

- The Woman in the White Kimono by Ana Johns - impulsively bought. A really interesting insight into life and love in post-war Japan.

- Storm Glass by Jeff Wheeler - read. A pleasant read set in a rich YA-ish world. The first book in a series I’ll be sure to revisit.

- Coffin Road by Peter May - read. If you haven’t read enough books that start with a man losing his memory and forgetting who he is, here’s another good one.

Things I’m loving

Films and shows:

- Parks & Recreation - People said that if you loved The Office (US) you’ll love Parks and Rec. People were correct.

- The Queen’s Gambit - The epic series that made the world fall in love with Chess again. I’m not kidding - sales of chess sets soared almost 300% and Chess.com gained 12.2 million new subscribers. I do wonder how many of those chess boards will be dust-free come summer.

Resources:

- Democratic Republic - If you weren’t aware, I’m the founder of an awesome business that sources delicious, direct-trade coffee from across Africa. We’re running a contest this week to win 3 bags of premium coffee, but there are lots of prizes to be won in the process!

- Radio Garden - Imagine Google Earth but instead of zooming into street view, you can zoom into public radio stations around the planet.

- Audible - I am yet to be crowned chief evangelist, but Audible is truly awesome for anyone who loves books. Make the most of the daily/weekly deals and start your digital stockpile!