I get messages from strangers all the time. That’s part of the fun of being on the internet. Many of those strangers become friends. But I’ll always remember one particular incident because it sparked my desire to learn openly, in public, and leave behind a trail of referencable learnings. I was once approached by a stranger who asked for advice on how to amass a war chest of savings and investments that would one day allow him to lead the life that he wanted.

To be honest, that's not what he actually asked, but it was the key to what he wanted to know. The original question was based on a presumption of my lifestyle - I seemed to be able to travel far and often. I took several trips a year to exotic places, documented well on Instagram, and owned a few nice things. This guy wanted to know how he could live a lifestyle like that. A life ‘like mine’.

I put ‘like mine’ in quotes because I certainly would not have characterized my life at the time in the same way he had. I was young, underpaid and overworked - hustling my way up the ladder of corporate law. I just happened to have developed a decent framework for saving effectively that allowed me a few comforts.

I tried to answer what I thought was the root of his question. I told him about the mechanisms I'd developed over the years that allowed me to budget, passively save and invest a substantial proportion of my salary.

The answer to how I travelled so often was admittedly harder to replicate. I had very intentionally started a travel business, organizing group trips for friends and strangers around the world. That business grew into a global community of +2000 travellers which allowed me to travel frequently and at a low cost. I developed ancillary skills to make sure that if my business didn't contribute to the cost of my travel then other businesses would. Comped hotel rooms, flight upgrades, festivals and celebrity parties came as a combination of my status as a travel entrepreneur, an influencer, and a photographer.

The point was, despite giving this person an entire playbook on my personal lifestyle management and business, he was not satisfied. In fact, he was angry.

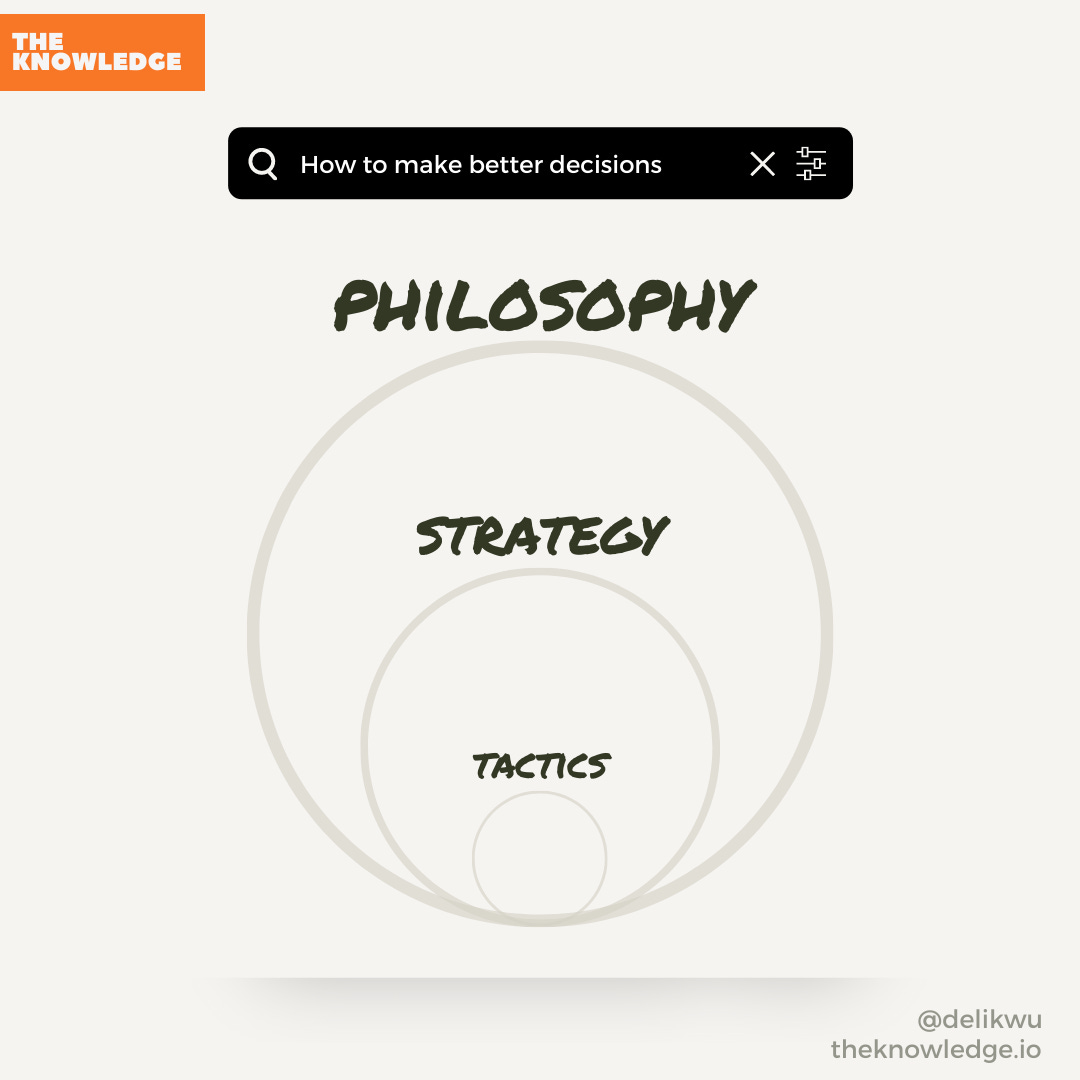

The truth is he wasn’t looking for knowledge - he was looking for a gimmick. He wanted tactics. Secrets. Anything he could apply immediately, or even throw money at, that would allow him to book a flight to Italy tomorrow. He pushed and prodded as though I was the gatekeeper to the Illuminati. That's when I realized that tactics don't matter at all. Strategy does—and beyond that, the underlying philosophy, mindset and approach.

Strategy before tactics

You can have all the tactics in the world but will only unlock a fraction of the results until you become the person you need to be to make the tactics effective.

Ideology without strategy is useless too. Faith without works is dead. You can't manifest your way to a dream life with 95% vibes and 5% skill.

The biggest key to unlocking insights, entrepreneurial success and great investment habits could probably boil down to developing a fundamental set of mental frameworks. If you have the right toolkit, you can attack any problem with the confidence that success is a matter of time and repetition.

Learning how to think and make better decisions will yield better rewards over time than any one area of knowledge you might apply yourself to. A toolkit for rigorous thinking is what allows 20% of effort to generate an extra 80% of value.

That isn’t to say that tactics themselves don't work, but simply that your capacity to execute them will be capped unless you learn the frameworks that lead to the right decisions.

Too many people obsess over finding out what 'successful people' do, instead of training themselves to understand why they do what they do. It's the why that unlocks the how. Knowing someone invested in a particular stock is completely meaningless outside of the context in which they made that decision - you need to understand their philosophy, their strategy, and the contextual knowledge they had when they made it.

If you're following and copying day-traders while trying to invest on a 20-year time horizon, you're setting yourself up for failure.

Simply knowing the decisions Jeff Bezos made as a leader means nothing unless you understand the mindset that drives those actions. Would he have made the same decision if he had different priorities? Would he have taken those same steps if the market timing was different? Once you understand the why you can extrapolate that knowledge into different contexts.

Suddenly the information can be weaponized; the knowledge is dangerous enough to be deployed. You can see the pattern beyond the move.

Chess masters drill themselves on a hundred openings and their variations. The best players know the difference between tactics that are useful in the middle of the game versus the endgame and develop the sensitivity to know when their immediate tactic is under a distant threat. Replicating their moves without understanding the patterns won't get you far.

Tactics change on the fly. Strategy is adjusted to your opponent. Philosophy evolves after 1000 repetitions.

Forget the tactics. Develop the tools. Become a robust thinker and become antifragile in the face of changing conditions.

Mental shortcuts

People frequently rely on biases as heuristics.

The beauty of heuristics is that they are abstractions that help us understand sets of information, and tell us where to put that information, or what actions to take. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that let us be lazy. This can be extremely useful. We’re inundated with data and decisions each day— we need abstractions to make sense of it all and to take action quickly. However, when the premise of a heuristic is faulty or out of date, it can lead us down the wrong path.

A quick example is authority bias and the halo effect. The halo effect is a cognitive bias in which our impression of a person characterizes how we feel about their traits.

The logic:

- We make false attributions about people we think are attractive, popular, tall, strong, etc.

- We assume people with these positive attributes have high social status.

- We assume people with high social status are successful.

- We assume that successful people make good decisions.

- We assume that if we make the same decisions as successful people, we will also be successful.

The heuristic:

- Do what the cool kids are doing.

Choosing to base your actions on the decisions of people you deem successful is a heuristic, but the shortcut is only as good as the thought process behind it.

Robust thinking

Be intentional in the heuristics you deploy. In the course of your life, you've likely encountered and adopted many frameworks of thinking without a second thought. Eat cereal in the morning. Eat dinner before dessert. Wear certain types of colours in certain types of settings. Buy this to signal that. Often we're barely conscious of the reason we do these things, but we forge on anyway.

Sometimes these shortcuts are valuable:

Brush your teeth every day – It doesn't matter if you enjoy the process. It's dental hygiene.

Often they're not:

Buy this bag because your favourite influencer bought it. – But do you like the bag? Is it useful? Can you wear it often? Can you afford it? Will it be on sale soon?

Invest in this stock because people keep tweeting about it. – But do you understand the thesis behind the move? Are your values aligned with the people pumping the price? Does this match your investment philosophy? Does it fit your time horizon?

Use gimmicks wisely

In the fields of cognitive development and experiential learning there's something called the learning loop, or learning cycle:

>> Interest > Conceptual Exploration > Integration > Reflection

>> Curiosity > Framing > Triangulation > Decision Making > Learning

>> Experience > Reflective Observation > Abstract Conceptualisation > Action

Different sources draw different models, but each is a variation of the same core process: There is a problem to solve - a new interest or experience. We explore and reflect on it. Then we abstract this information into something digestible - this is the heuristic - the gameplan, tactic, or frame that allows us to make a judgment. Then we act. With that action comes a new experience or problem, and the cycle continues.

When facing a decision we’re often drawn straight to the abstraction because it's easy to follow. In trying to find the answer we look for tactics others have used - what was the trick? the abstraction?

Skipping to the abstraction removes the opportunity to pattern match. It turns tools into gimmicks. The gimmick in a video game is finding an NPC who will always give you side quests, or finding the low-level monsters that always drop gold. Gimmicks have their place, but they’re only useful in a limited context.

Pattern matching lets us know when to follow the plan and when to deviate from it.

Interrogate your shoulds

Contrary to what we’re taught in school, in life, there are no concrete answers. The only reliable answer is: 'it depends’. Asking a friend what they're wearing to an event is a much easier shortcut than thinking through all the variables for ourselves. What’s the weather like? What transport am I taking? Will I be walking for a while? Who will be there? What’s the social context? What’s been washed? What’s comfortable? Uncertainty is scary.

From a young age, we're conditioned to believe there is always a right answer. As adults, we become scared of getting things wrong.

Once we get a 'right answer' we’re taught to stop thinking. Objective complete. We rarely pause to revisit our answers in light of new information (Bayesian thinking). We let cognitive bias and heuristics do the heavy lifting. When we can't find clear answers we become paralyzed because we've forgotten how to reason.

Investigate the things you tell yourself you ought to do - interrogate your 'shoulds'. Whenever you catch yourself skipping logical steps to make a decision about something you should do, think about where that ‘should’ come from and if the heuristic is still worth holding on to.

Secretly, we like being told what to do. We want to fit in. We need confirmation. It’s been this way since the first day of school, and even before that. When babies encounter something new they point at it and look at you. They’re asking: can you see what I’m seeing? Are we sharing this experience?

We implicitly look for signals from peers and people we admire that can tell us what to do, and how to react.

TL;DR

Don't become over-reliant on outdated heuristics.

Interrogate your mental models.

Ask questions at higher levels of magnitude to make decisions with greater levels of impact.

Don’t fall for gimmicks. Learning to pattern-match will yield greater rewards than skipping to tactics and abstraction.

React to this issue by clicking an emoji: 😍 | 🤯 | 👍 | 😴 | 👎 | 😡

If you have any thoughts on bias and rigorous thinking I’d love to hear from you! Reply via email, leave a comment, or send me a tweet!

I’d also love any thoughts on what I should write about next.

Read on for this week’s recommendations >>

Reading list

Books I’ve read/seen/will impulsively buy and add to my “to read” shelf on Goodreads. Recommendations from newsletter readers are always welcome:

- Skip the Line by James Altucher - seen. I’ve been absorbing the key ideas from this book through James’ podcast, and already know it’s going to be a great read.

- Start with Why by Simon Sinek - impulsively bought. Hearing about Simon Sinek’s secret rivalry with Adam Grant made me want to dig into the rest of his work. Start with Why has become a manual on leadership.

- Effortless by Greg McKeown - impulsively bought. The sequel to a book I devoured in 24 hours. I’ve already stolen ideas and frameworks from this book.

To win a book from the reading list backlog, click here